TOC and I: Using Systems Thinking to Understand Impact

Abstract illustration showing interconnected boxes and swirling lines against a grayscale background, suggesting a complex system or network of relationships

Okay, so I’m deep down a rabbit hole. 🕳️

On the back of writing about team information flows, I realised that I had done a lot of mulling on the things business analysts do — the parts and components — but little real thinking about the system Business Analysts work within. This realisation meant that I’ve spent the last month in a mad panic where I’ve simultaneously tried to teach myself systems thinking, and also to apply systems thinking to the BA role.

I’m not entirely sure it worked. But at the very least I learned a bunch, created some sweet diagrams, and made what feels like a minor breakthrough!

So if you are mad enough to join me down the rabbit hole, keep reading.

An intro to systems thinking

Like most BAs or thinkers of any kind, when I first came across systems thinking, I had a yeah, of course reaction.

Systems thinking is a way of making sense of the complexity of reality by looking at it in terms of wholes and relationships, rather than by breaking it down into its parts.

In short, systems thinking is an approach that focuses on the interplay between things, not just the things themselves. You know: understand the context before messing with things … blah blah blah … all very natural BA stuff.

A system is never the sum of its parts; it’s the product of their interaction.

You might have already come across systems thinking, theory of constraints, and current reality trees. Maybe you've even used them in anger.

If that's the case, feel free to skip the context setting. But if not, then let's dive into systems thinking — and, more specifically, the theory of constraints.

The theory of constaints

Within the umbrella of systems thinking

, there is a management theory called the Theory of Constraints (TOC), created by Dr. Eliyahu Goldratt. The central idea of TOC is that every system has constraints, and that reducing the impact of a constraint is the most effective way to improve the system.

And like all (read: none) great thinkers, Goldratt chose to explain his ideas as a novel. No, I am not at all joking, and boy was I surprised when what I thought was the fictional introduction added for engagement purposes just kept on going and going … for an entire book.

Luckily, it is not the only method he used to communicate his ideas, and there are plenty of books, videos, and thinks on his theories — thank lawd!

Within TOC there are five logical tools:

- The current reality tree,

- the future reality tree,

- the prerequisite tree,

- the transition tree, and the

- the evaporating cloud.

Side note: Best named logical tools, no?

For this article, I’ve focused primarily on the Current Reality Tree (CRT) as I was mostly interested in understanding how business analysis affects the system.

Growing a reality tree

A reality tree (RT) is, at heart, a cause-and-effect diagram. It maps the relationships between undesirable symptoms to identify root causes. Of course, there’s a bunch more to constructing a good reality tree — including logical tests up the wazoo — but at heart, they are a cause-and-effect diagram.

Like other root cause analysis tools, current reality trees are really powerful. By being explicit about what is being observed in the system, you are forced to re-examine what is happening and the assumptions that you are making. And the theory of constraints believes that by identifying the root causes, you can focus attention on resolving the correct problem while receiving the maximum benefit for your efforts.

Which all sounds great!

But mapping reality is not simple, because reality refuses to cooperate. This is why context diagrams are considered a recommended — if not required — step when establishing a project.

But compared to the logical foundations of a reality tree, context diagrams feel like child’s play.

The TOC thinking process is composed of logical tools. The emphasis here is on the word

logicfor good reason. A lot of problem-analysis tools use graphical representations. Flowcharts,fishbonediagrams, and tree and affinity diagrams are typical examples. But none of these diagrams are, strictly speaking, logic tools, because they don’t incorporate any rigorous criteria for validating the connections between one element and another. In most cases, they’re somebody’s perception of the relationship.

Yeah that's right. Dettmer just threw some serious shade at you and your illogical analytical approach. Want to play with systems thinking? You have to bring the rigour.

So bring it! 👏

It's actually not that scary!

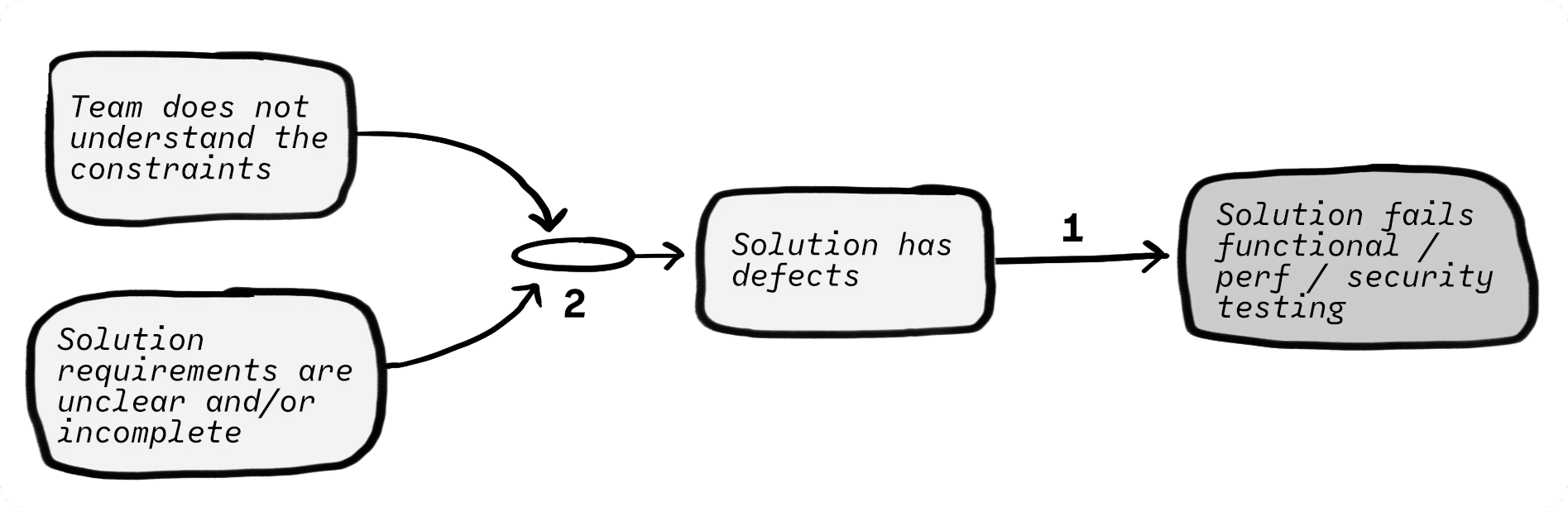

Once you get the hang of reality trees, they are relatively easy to read. The boxes are statements about an observable effect, and the arrows show the causal relationship between two effects. An effect without a cause is a root cause.

To read, refer to boxes as IF

, arrows as THEN

and circles as AND

. Some examples:

- IF

Solution has defects

, THENSolution fails functional / perf / security testing

. - IF

Team does not understand the constraints

ANDSolution requirements are unclear and/or incomplete

, THENSolution has defects

.

Okay, enough context …

Let’s get to the point.

The reason I went down this systems thinking causal map rabbit hole is because I wanted to understand how business analysis influences the systems within which it is done. And I wanted to do that in a way that permitted me to reason about it. It is all well and good to claim that we’re instrumental, but proving it would be better, no?

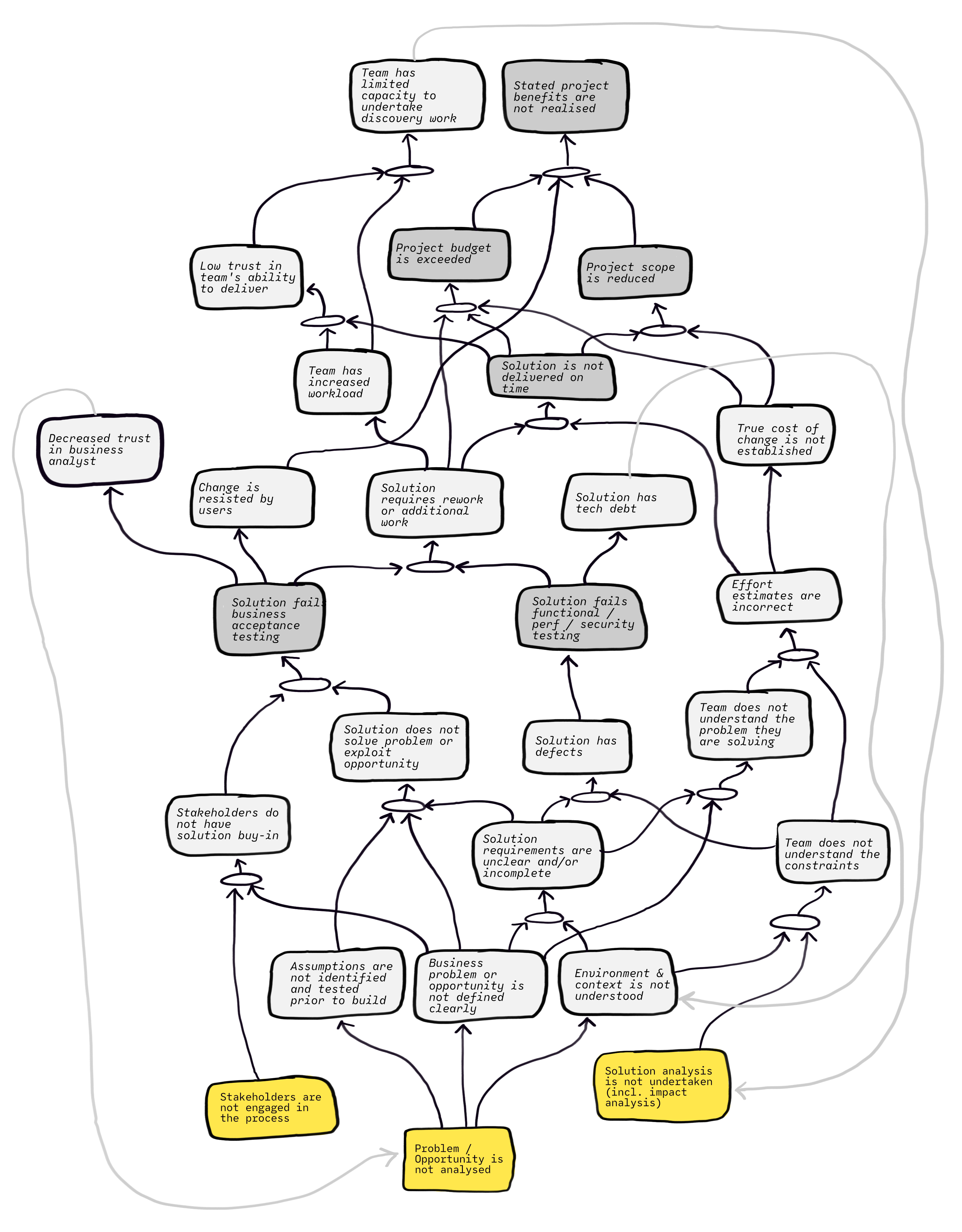

So, I created a (hypothetical) current reality tree for all the things that go wrong with business analysis work based on my experience. Call it a mash up of the bad things that I’ve seen more than once.

Now it is important to note up front that I am wildly self taught in this method! And perhaps even more importantly, this is a hack. The CRT approach is designed to surface how the different parts of a real system work together, and here I’m using it to understand how things can go wrong. So I’ve included more unhappy stuff than you’d usually include.

Knock on wood. 🤞

As a result, many of the ANDs

I would read as AND/ORs

because it is less likely that both will occur in the real world, but either could contribute to the unintended consequence. For example, both Solution requires rework

OR Effort estimates are incorrect

can result in Solution not delivered on time

. Or both, of course.

And for the map, I started with the following six big undesirable effects:

- Stated project benefits are not realised

- Solution fails functional, performance, and/or security testing

- Project budget is exceeded

- Solution is not delivered on time

- Solution fails business acceptance testing

- Project scope is reduced

But with all those disclaimers out of the way, here’s the whole map. I don’t think it is too overly dramatic to say:

Welcome to project hell!

Tracing back from those six undesired effects turned into this whole mess. 👇

Yeah, that's a special kind of gross!

But what’s most interesting is that if we trace back from our undesirable effects — picking reasonable causes and symptoms along the way — then we eventually end up with just three root causes.

- Stakeholders not engaged in the process.

- Problem or opportunity is not analysed.

- Solution analysis not undertaken.

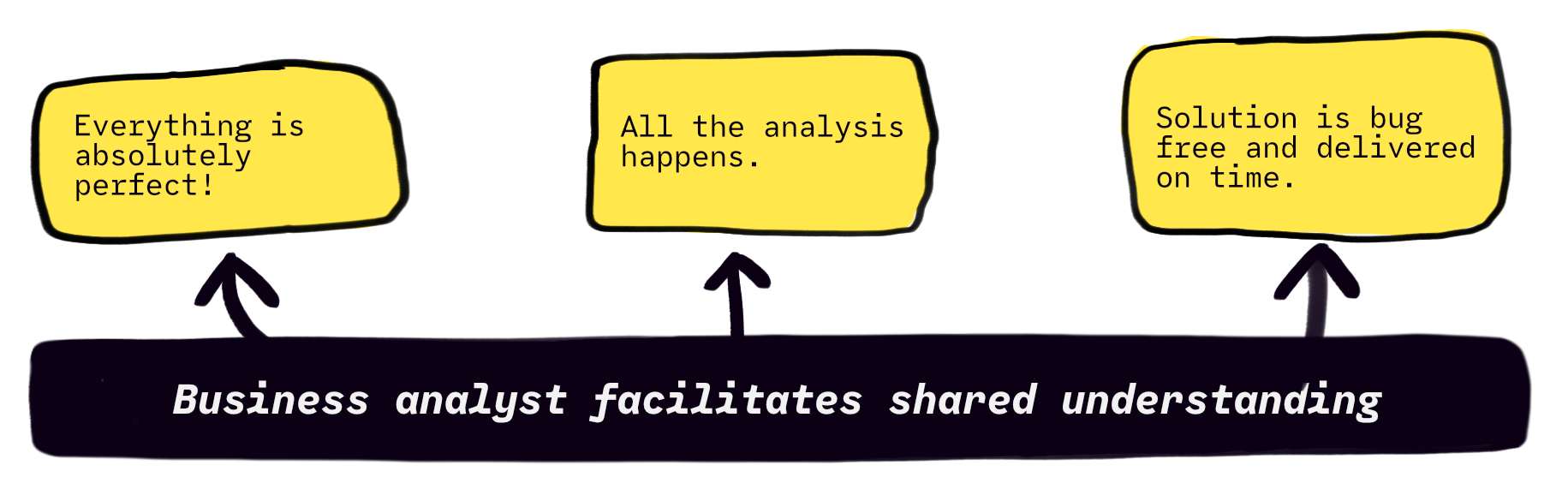

But why stop there? Yulia Kosarenko claims that the most important thing business analysis delivers is shared understanding across all stakeholders. And what's underlying these three big bads?

Yip. Us.

Business analysts have an outsized impact on the entire delivery system.

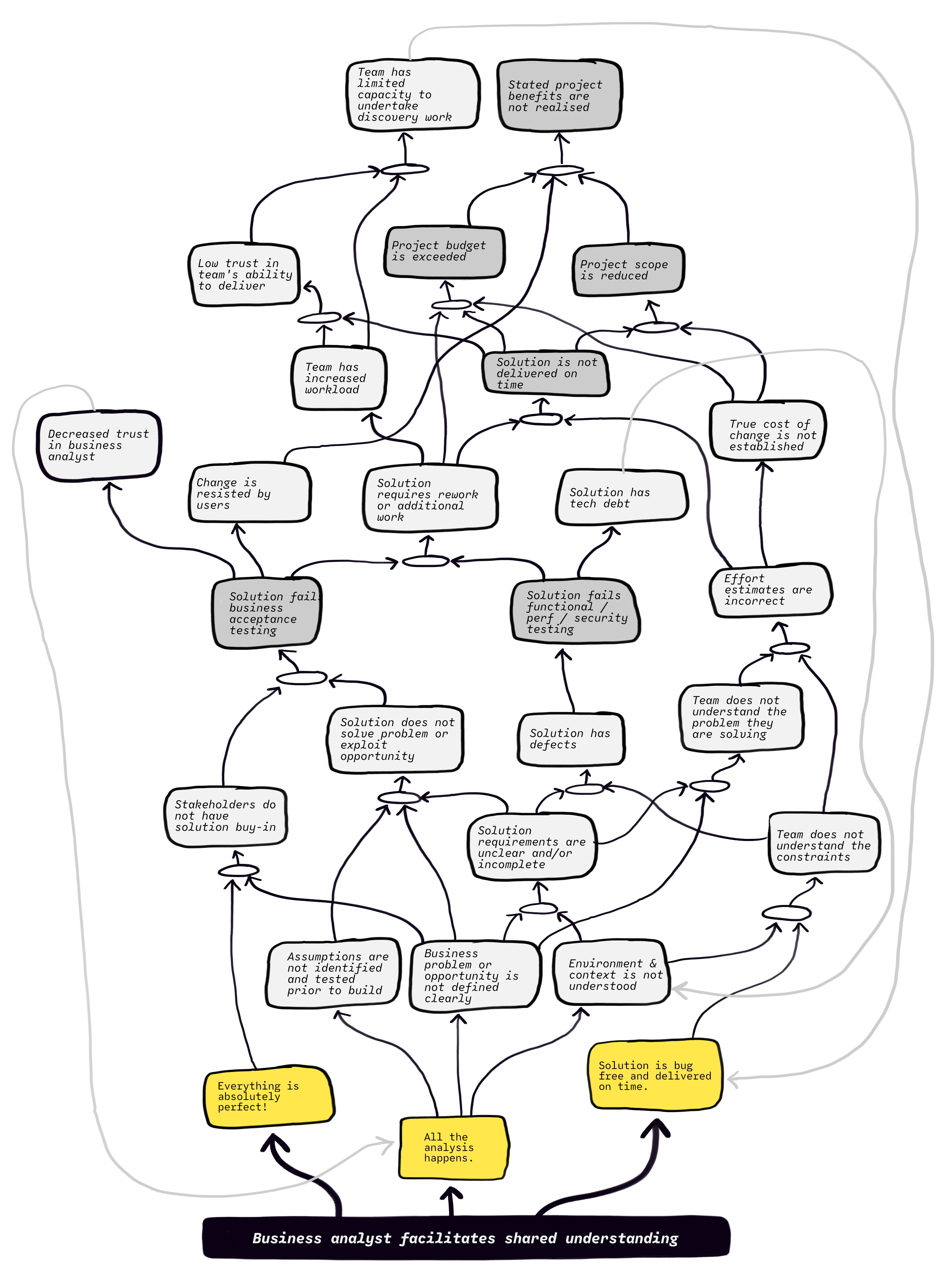

I don’t want to Han-splain™ to you how to tackle these root causes. Especially since any advice would have to be contextual to be of any value to you. But I do want to show you what this map looks like when the business analysis is Done Well™.

Welcome to project heaven!

The following is the future reality tree (FRT) for when you build shared understanding.

I jest, of course.

The truth is that Business Analysts operate in a complex system where every good outcome is predicated on many other things also going right — good development, good testing, good everything. Doing our job and doing it well is necessary, but, sadly, not necessarily suffcient to delivering value.

Yeah, I knew I was great … so what?

Okay, okay, okay! So what does this all mean?

Simple: we are too easily distracted from the what by the how.

We get obsessed with techniques. And we forget that the requirements don’t matter — but the shared understanding of the problem, scope, and options do. And equally, the stakeholder map doesn’t matter, but the relationships do. The as-built document format doesn’t matter, but the IP it represents absolutely does.

Now I’m as bad as any BA. I have my preferred approaches to all of the above. But I shouldn’t.

First, I should ask Why?

, then What?

, and only then, How?

. Because the performance of a system depends on how the parts work together, not on how they act independently.

If we focus only on the artefacts that we create and ignore the system in which we work, then we might not see the impact that we’re having. But to avoid that, we first need to see the system. Only then can we focus on the right things. That’s where systems thinking can help.

But if you're looking at the insane diagrams I did above and wondering if I didn't actually go a tad mad while writing this article — and if you aren't especially interested in joining me — then let me remind you what the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland said:

Oh, you can’t help that,said the Cat:we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.

How do you know I’m mad?said Alice.

You must be,said the Cat,or you wouldn’t have come here.

Read more

Here’s a selection of resources I’ve been using.

- WTF is … systems thinking by

- Systems Thinking for Happy Staff and Elated Customers by (video)

- Current Reality Trees to Lift the Fog of War by

- Thinking in Systems by

- Using a current reality tree by

- Theory of constraints

- Thinking in Systems by

- Thinking for a Change: Putting the TOC Thinking Processes to Use by

Last updated .