Impaired Function: Understanding the Impact of Dysfunction

An illustration of a row of townhouses. The one on the left is nice and well maintained, but the houses get less and less maintained and the one at the far right is really run down.

In my last article I crowned context “king”.

But as I was doing the thinking for that article, I had this extremely irritating and insistent voice in my head saying yeah, but you know that’s not how it actually works

. And even as I hit publish, I knew that the annoying voice was (very annoyingly) correct.

This isn’t how it actually works. At least not all the time.

I focused on a single axis because you have to start somewhere. A single dimension could never capture all the nuance of the world we work in; our systems are n-dimensional. I deliberately ignored and stripped away other dimensions to simplify and focus on one element, namely, levels of process and standardisation within an organisation.

But just because you choose to ignore something doesn’t mean it goes away.

So, this article addresses the missing part by adding a second part to this series on context: because if context is king, dysfunction is queen.

What is dysfunction?

Everyone has some experience with dysfunction, either at work or in life. Dysfunction is a word that has a visceral connotation; you can sort of feel the word.

But what do we mean by dysfunction in a work context?

Workplace dysfunction is when the system isn’t working as it is meant to work. Roles in practice are not what their job descriptions say they are. Decisions aren’t made in the forum where the org structure says that they should be. The person with the power in the room isn’t the person with the title. Funding conversations happen offline and politics are everywhere.

It’s a matter of degree. A system can be a little dysfunctional, or a lot.

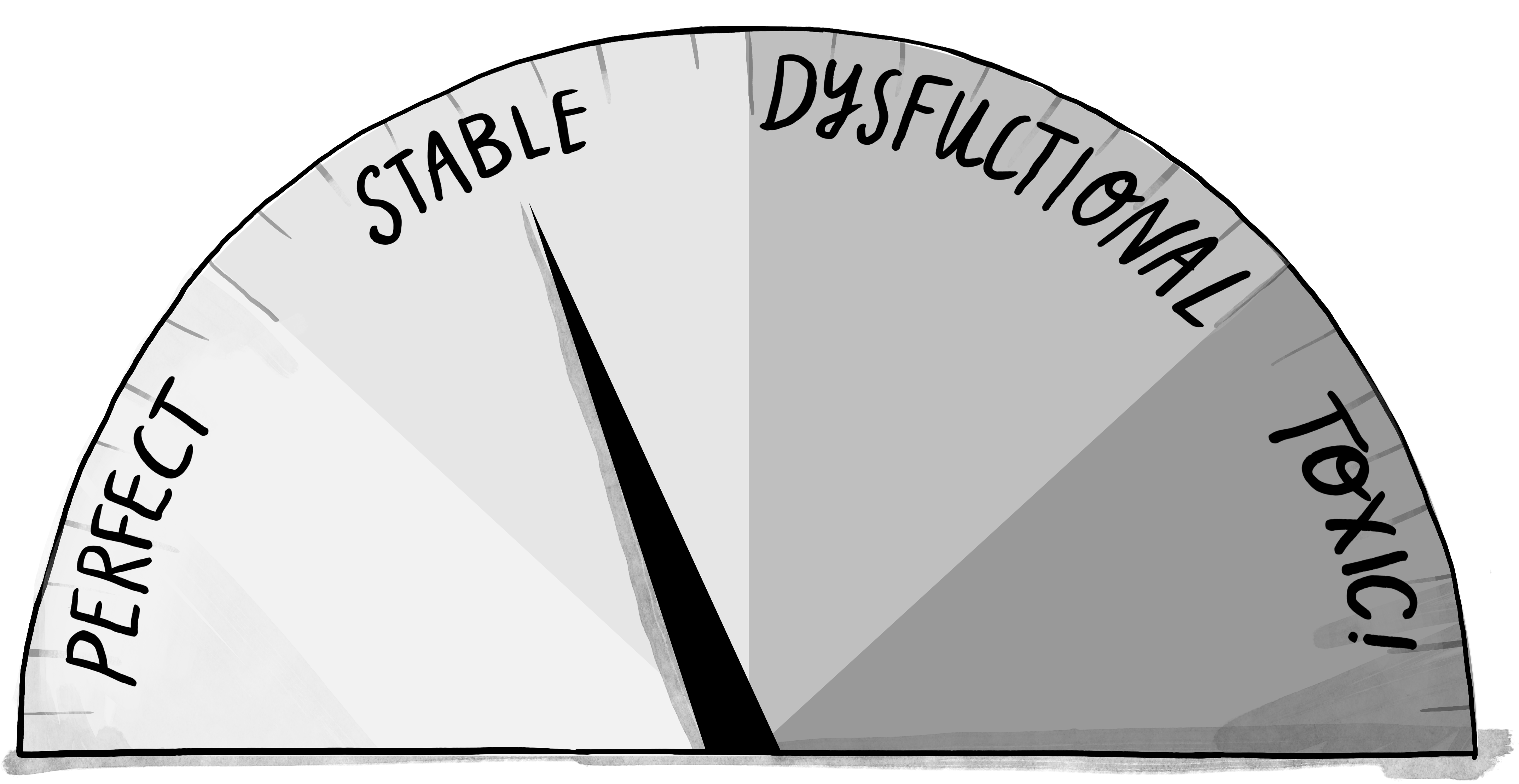

Introducing the dysfunction scale

As soon as I started talking, thinking, mulling, chatting about this concept, I imagined a dysfunction meter. I simply had to draw it! Introducing the Dysfunctiometer!

We all know that in a continuum, the placement of boundaries is somewhat arbitrary, but for sake of simplicity I’ve split the dysfunction scale into four different bands to permit us to talk about them.

Let’s start at the far left where everything is happy, green, and dreamy …

🟢 A perfect system

Ah, the mystical perfect system! A perfect system is lean and mean. People act entirely within their roles. They don’t have too much work. Things are smooth, and there’s no need for multiple layers of control.

In a perfect system, if someone has a question, then they can simply contact the responsible person to get an answer. Concerns are raised, and the system has the necessary feedback loops to correct course.

From what I’ve seen, perfect systems are rare, but I’ve certainly experienced elements of them in the wild, and I’ve definitely seen parts of a system run perfectly. Its really reassuring that smooth sailing is actually possible!

The very definition of dreamy!

But of course we are just at the very lowest levels of the Dysfunctionmeter … so let’s dial it up a notch!

🟡 Stable systems

Stable systems have some dysfunction, but aren’t in-and-of-themselves dysfunctional! Stable systems have some characteristics that mean that they can’t quite operate optimally if left alone.

Examples include:

- The tech is complicated and there are multiple teams working on the same codebase.

- The business is complex enough to require discussions across different areas to understand what is required.

- The system isn’t quite resourced in a way that enables smooth sailing: people have to step out of their core roles to keep things moving.

Stable systems are super common and they just need a bit of help!

Help can take many forms, but most commonly it includes adding facilitators, process, more specialised roles, and usually, a few checkpoints to ensure that we’re on track.

With the right help, a stable system can function as well as a perfect system. And that’s typically what you’re trying to achieve — you’re attempting to counter the effects of the challenges on the flow of value.

Every system is different, and selecting the right interventions is the key to getting a good result. For a stable system, you’re just adding support to the existing system, not making changes to the system itself. The system is imbalanced, not actually flawed!

And when a stable system starts to hum, and starts to work as well as a perfect system, you know you have your interventions spot on!

If you’ve been following along from last month’s article, here’s the overlap! In Context is King, I posited that most Business Analysts operate in Established systems and that most advice is geared towards that environment. I believe it is also fair to claim that most Business Analyst advice is assuming a stable system in an Established environment.

Things are slightly less easy to manage as we dial up the dysfunction …

🔴 Dysfunctional systems

A dysfunctional system is a system that’s got significant enough challenges that just adding some support ins’t gonna fix it. A dysfunctional system requires intervention to the system itself to work effectively. With substantial effort, the system can work as well as a stable system, but it can’t get to perfect without serious intervention.

One of the earliest signs of a dysfunctional system is that some or even most of the team members regularly need to work late to keep things moving. Staying late — and that doing so is a necessity — is a sign that the system isn’t resourced correctly. Incorrect resourcing is perhaps the lowest form of dysfunction.

Other slightly more dysfunctional examples include:

- Dependencies between teams are so significant that work is often held up waiting for other parts of the puzzle to be delivered.

- There aren’t clear accountabilities and responsibilities, so decisions keep getting re-litigated. The roadmap keeps changing.

- Key skills are missing from the team, so people are acting in roles for which they lack the core competencies.

- People are hesitant to talk openly about the issues.

- People are protective of their patch.

Where a stable system can be neutral (energy wise), a dysfunctional system is not. People burn out, are stressed, and work is just hard.

Another — somewhat surprising — way to tell that you’re in a dysfunctional system is the presence of heroes.

We need to talk about the hero in the room …

You know the person I’m talking about. Works late and single-handedly pulls together a plan to get you out of the mess. People talk breathlessly about how we couldn’t have done it without them. Everyone goes to them for the details. And their name gets thrown around as the fix for everything.

You might have even been a hero at one point — it was stressful, no?

And if there are heroes, there are likely also villains.

You know who I’m talking about! Everyone knows that these villains are causing problems! They aren’t performing their roles, but there’s no performance management in sight. Their poor performance is openly acknowledged — at least behind their backs. People are annoyed by the negative impact. They avoid dealing with the villains directly.

But this article isn’t about individuals; today we’re interested in the system, and what having heroes (and villains) tells you about the system. And the presence of heros and villains tells you that your system is broken enough to create them.

That hero is your system’s most likely point of failure. They are hiding the system weaknesses. They introduce artificial conditions into the system and make it harder for the true systemic issues to be recognised. And if you can’t get the issues acknowledged, good luck actually getting a mandate to make the necessary changes.

When you think about it, you’ll notice that heroes — no matter how hard or well they work — never actually manage to fix things. And that’s because they’re just making things appear okay, however temporarily.

Villains do a similar thing but in the opposite direction. They collect blame about what isn’t working, they become the target of people’s frustration. And because we all know it’s their fault, people stop looking for the actual underlying root causes. It’s the system that enables poor performance. No one chooses to suck at their job.

In short, heros and villains are not good news.

Instead of heroics or simply attributing blame, a Dysfunctional system needs changes to the system itself to stabilise. Just working within the system won’t move the needle.

Without intervening at the system level, the system is likely to deteriorate further. And if it deteriorates too much, then you’ll end up with a toxic system.

⚫️ Toxic systems

The most dysfunctional systems are toxic.

A toxic system has deteriorated to the point where interacting with the system isn’t good for anyone. Things are seriously wrong. What the system delivers and its stated goals are wildly divergent. The system needs dramatic changes to get better. Think: people leaving, major process changes, and likely a cultural reset.

Examples include:

- There is visible tension between teams and departments over priorities and the work.

- Priorities appear to be more about what is good for the people in power, and not for the organisation itself. Politics abound.

- People are stressed, and it isn’t uncommon for tempers to flare.

- No one wants to make decisions because they fear being blamed when things (inevitably) go wrong.

- The team is chronically under resourced.

- There is significant pressure to report that everything is fine. Reality and reports diverge accordingly.

Which is all to say: the system is borked. Like really borked. It doesn’t matter how excellent you are at your job, unless you have serious mandate to pull the system apart, there is little you can actually do to help. At best you can keep it limping.

And even getting to a limp will likely take significant effort.

You should be asking yourself some hard questions about whether it is worth it. The reality is that unless you’re the CEO or someone seriously powerful — and maybe not even then — toxic systems should be avoided at all costs.

Yeah so, why does this matter?

But now that we’ve maxed out the dysfunctiometer, it’s time to step back and ask, what’s the point of this discussion?

The reason that dysfunction is such an important topic for Business Analysts is because in a truly perfect system, one with absolutely zero dysfunction, our middle-person type roles wouldn’t be required.

No, really. Think about it!

In an ideal world, in a perfect system, managers and decision makers have the skills and time to analyse situations properly, clarify their needs, identify options, and shape solutions. In that ideal world, they’d have time and functional relationships with the development teams and would be able to work with them to deliver solutions that were fit for purpose!

In a perfect system, we aren’t required — because the system works perfectly!

The truth is, those of us who work in the middle space require some dysfunction in the system to exist to be helpful. The dysfunction

could be minor — maybe the Product Manager just doesn’t have the time for all the deep-dive analysis needed to make good decisions.

Or it could be that there are just too many stakeholders involved for one person to manage all the relationships and information. Or the technical team prefers to focus on the solution and doesn’t want to take time away from the tools to get answers from SMEs.

And in those situations, we are helpful!

But this means that by the time we arrive on the scene, there is already some dysfunction at play.

And like the proverbial frog, it can be hard to tell when the water is getting too hot!

Temperature check

Dysfunction is easy to identify in other people’s environments, but much harder to spot in our own.

There are lots of reasons for that, but much of it comes down to all the expectations that we carry around! We should have found the cause. We should have delivered on time. We should have done that faster. We should have spent more time with our kids/friends/partner/cat. We should be better. We should get more done. We should, should, should.

And then we project these expectations onto our environment and then proceed to experience stress when reality and our expectations don’t line up — gosh it must have been that I misunderstood what was happening there, or I should have approached that differently

.

And if we aren’t projecting, then we are normalising the dysfunction — as in, aren’t all team meetings stressful?

Experience helps you to identify abnormalities in the system. The ability to avoid the shoulds and to see objectively how the system is working is a muscle you need to train. And if you’re having difficulty, sometimes it is easier to practice being objective with your previous work environments (it is amazing what a couple of years of separation can do for objectivity).

Knowing your environment is helpful to understanding how to help it.

But this is missing another key part of the equation …

What’s your spice tolerance?

Knowing what environment you’re in is like knowing what the chilli pepper icons mean on hot sauce bottles. For that information to be useful, you need to know what your own personal spice tolerance is. If you are ordering dinner, do you avoid the spicy foods? Or do you like a bit of spice so order medium? Or do you like living dangerously and order the five-alarm fire dish?

Your preference is neither right nor wrong: it just is. Each of us is different. What is fun for one person might be boring for another. And what might be way too intense for one person might feel like a genuinely fun challenge to another!

But it isn’t just preference! There’s a component of this that’s comparable to having a tolerance level. There’s a certain level of spice that your body copes with, and a level that isn’t fun!

But unlike a spice tolerance level: Your tolerance is somewhat flexible

I love me a somewhat dysfunctional environment — I think navigating the complex system is fascinating. But that statement comes with a huge caveat: I love a dysfunctional environment where I have the support to make a positive impact!

Without support or mandate, the dysfunction is just depressing because I can’t do anything about it! There is nothing worse than slaving away and knowing that it’s not actually going to move+ the needle.

The point is, there’s a ton of factors that can increase or decrease your tolerance: having a mandate or a very supportive boss will increase your tolerance, but if your home life is under pressure, then that will deplete your tolerance.

So it’s not just knowing your preferences, but also keeping within your own personal tolerance levels. Or if you have to operate outside of your levels, being kind to yourself and making sure you are doing good self care (while you navigate your way to safer waters).

The way I see it, it is hard to be anyone other than you, so you should do you well!

Last thoughts!

Phew! I did not think it was going to be a long article when I started, and yet here I am some two and a half thousand words later! Turns out I have no idea how many words are in any single topic. And I’ll stop adding to them now.

But I’ll leave you with a reminder that you have way more agency in your journey than you probably believe. And being able to judge accurately what you can — and what you want — to deal with is an incredibly powerful part of that.

Some things to keep in mind along the way:

- Your preferences are your own.

- You can only position yourself well if you know what

well

looks like for you! - Some environments are never worth it.

Last updated .