Context is King: A Deep Dive into What “It Depends” Depends On

An illustration of a landscape. On the left are mountains and wilderness, the middle has a plain with some houses and farms, and the right has a cityscape.

Two things are pretty much always true: doing great work is context-dependent, and not all environments are the same. So why does best practice

pretend that context doesn’t matter?

Here we dive into context and put forward a model for working out what your current context is. Because if you’re like me, you probably gravitate towards places and spaces that are a bit odd. And therefore more fun!

Come for a walk with me into the wilderness of context …

Situation dependent …

Most of the activities that we typically label business analysis

are undertaken in large, established organisations. Similarly, the Business Analyst role usually exists only when the organisation is big enough to justify having a person dedicated to carrying out business analysis activities.

Our role is the result of economies of scale. This creates some interesting consequences.

Not the least of which is that a lot of the how to

content for business analysis is geared toward a well-established and ordered environment. We have international bodies who create, standardise, and recommend best practices for business analysis to Business Analyst professionals.

But best practice

isn’t always applicable: the Cynefin sense-making framework describes five domains (environments), but they assign best practice

only to one of them.

Singular.

One.

And as all environments — a bit like entropy — tend towards commodification and standardisation, the best practice will likely be applicable eventually. But that leaves us with a ton of business analysis content that is applicable only if you are operating in an ordered environment.

So what do you do when you’re in one of those other environments?

Well, you muddle your way through like I did!

And while you do that, there will be a delta between what you’ll read and what you’ll experience. If I had to boil down my motivation to write and share about business analysis into a single factor, it would be that I don’t see myself or my own experiences out there much. There’s plenty of best practice

, but not a lot of real world.

But before we talk about different ways to tackle problems, we first need to consider the different contexts. Because I’m not saying that best practice

isn’t best practice, I’m saying that best practice depends on the context. And that context can vary dramatically.

And if you need to understand your context first, then it helps to have a model.

That’s precisely what this article attempts to do: to provide a model to help us to think about the context in which we’re working, so we can determine which best practices apply in our situation. Now, there’s a bunch of existing frameworks for understanding your context and several that I particularly like and to which I keep returning — links to references are at the end of this article. You’ll see strong influences from these references, but simplified and repackaged in a way that’s helpful, I hope, for talking about business analysis.

And all of the models — including the one we’ve compiled — simply help you to ask yourself one big question: Where are you? What, precisely, is your context?

And to answer that question, I want you to come for a (metaphorical) walk with me! We’re going to start where most people live … in the city.

Established 🏢 🏘️ 🌳

A city is established. Built. There are paved streets. Dirt is only found in manicured gardens. Office buildings, billboards, roads, traffic lights, and billboards abound. Services are commodified, infrastructure is not only everywhere, but deeply integrated and available; water is piped, along with gas, electricity, internet, and sometimes people!

There are rules and signs and everything is known, documented, and tracked in minute detail at the various municipal offices. Changes require consultation and consent, and parts of the city are so old and full of heritage buildings that the very idea of change — or even worse, modernisation

— is frowned upon.

A city is a established, ordered, environment.

And in an established work environment, things are similarly ordered and controlled: processes and infrastructure exist and best practice is king. Here we have known knowns and we build on what already exists. Boundaries and rules are explicit, there are approved ways of doing things, and there’s usually a right answer based on information, data, and past experience.

Most large companies, enterprises, government agencies, and multinational corporations are established work environments.

Signs you’re in an established environment:

- There was a comprehensive onboarding process for your role

- You have a clearly defined job description and there are payment bands

- There’s a community of practice for your role; and it has clout!

- Everything has a defined and documented processes

- There’s templates for everything and you are mandated to use them

- There’s an EPMO, PMO, or some other scaled delivery model such as SAFe.

- There’s a regulated path to production with stage-gates

- Governance is a real thing!

If this sounds like where you work, then congrats! You’re in an established environment!

You’ve got good company: most people live in cities, and similarly, most people work in established environments. The vast majority of business analysis is undertaken here and happily, the vast majority of business analysis guides assume that you’re here.

Emergent 🏡 🌱

If we keep traveling, then we might end up leaving the city, and out here things are a little different. While there will still be some access to infrastructure, it might not be as readily available. Instead of piped gas, you might need to get canisters delivered. Instead of one-way-streets and traffic lights, there are roundabouts and country roads. To cross the road you don’t look for a pedestrian crossing, you’re responsible for looking both ways for traffic.

Eventually paved roads give way to long gravel driveways and glimpses of lights tucked away through the trees. Sections become bigger and while there are still rules, there are more possibilities for how to tackle things. Maps of the area are available, but they don’t have the detail that the city maps do. Who knows what you’ll find if you start digging?

The country is an emergent environment.

And in an emergent work environment, things are known, but evolving: there are no right

answers, just choices and tradeoffs. The rules are a little more malleable, and good or emergent practice is king. Because of the squishy rules, there are fewer constraints.

There might be sensible ways to tackle things, but there is no one path that you must follow. You’re living and breathing known-unknowns.

Signs you’re in an emergent environment:

- Onboarding to your role was a bit ad-hoc

- There are established role definitions, but people have some flexibility

- If there is a Business Analyst community, the focus is more on socialising and support than on standards of practice

- There are some processes, but they’re not always documented or enforced

- There are templates available to reference

- Delivery process is dependent on the work and subject to change

- There may be informalities around governance practices!

If this sounds vaguely like you, then you’re in an emergent environment!

Most small or medium enterprises, digital agencies, and ventures are in some way, shape, or form, emergent. And many big corporations have departments or projects or areas that are essentially emergent.

If the majority of Business Analysts work in established environments, most of the rest operate here!

Esoteric 🌤️ ⛰️

If you keep walking, you’ll eventually run out of, well, everything! The roads become narrow and unpaved, then run out. You’re on your own. There are no rules here other than staying alive, and the maps say here be dragons.

You’re in new territory. You have no existing infrastructure, no rules, no constraints, and only entirely novel practice. You have to try something, learn from it, then adapt your approach.

In an esoteric work environment there are almost no constraints, therefore the possibilities are almost limitless. Novel practice will help you to navigate the complexity. In an esoteric environment you’re surrounded by unknown unknowns. The rules are guidelines at best!

Signs you’re in an esoteric environment:

- Um, sorry, what onboarding??

- Roles are not clearly defined, people just play to their strengths

- No active BA community — you might even be the only BA in the place

- No defined expectations for the work

- Templates? You mean the things you can load in Miro?

- Delivery process is truly agile

- Decisions are made as needed by the people impacted

Sound like your situation? Then perhaps you’re in the esoteric zone.

If you are, then know that you’re operating outside the norm for most Business Analysts — which might be pleasing or might be distressing depending on your personality type. Business Analysts working here might not even think of themselves as BAs and little to none of the normal business analysis advice applies.

The boundaries are arbitary

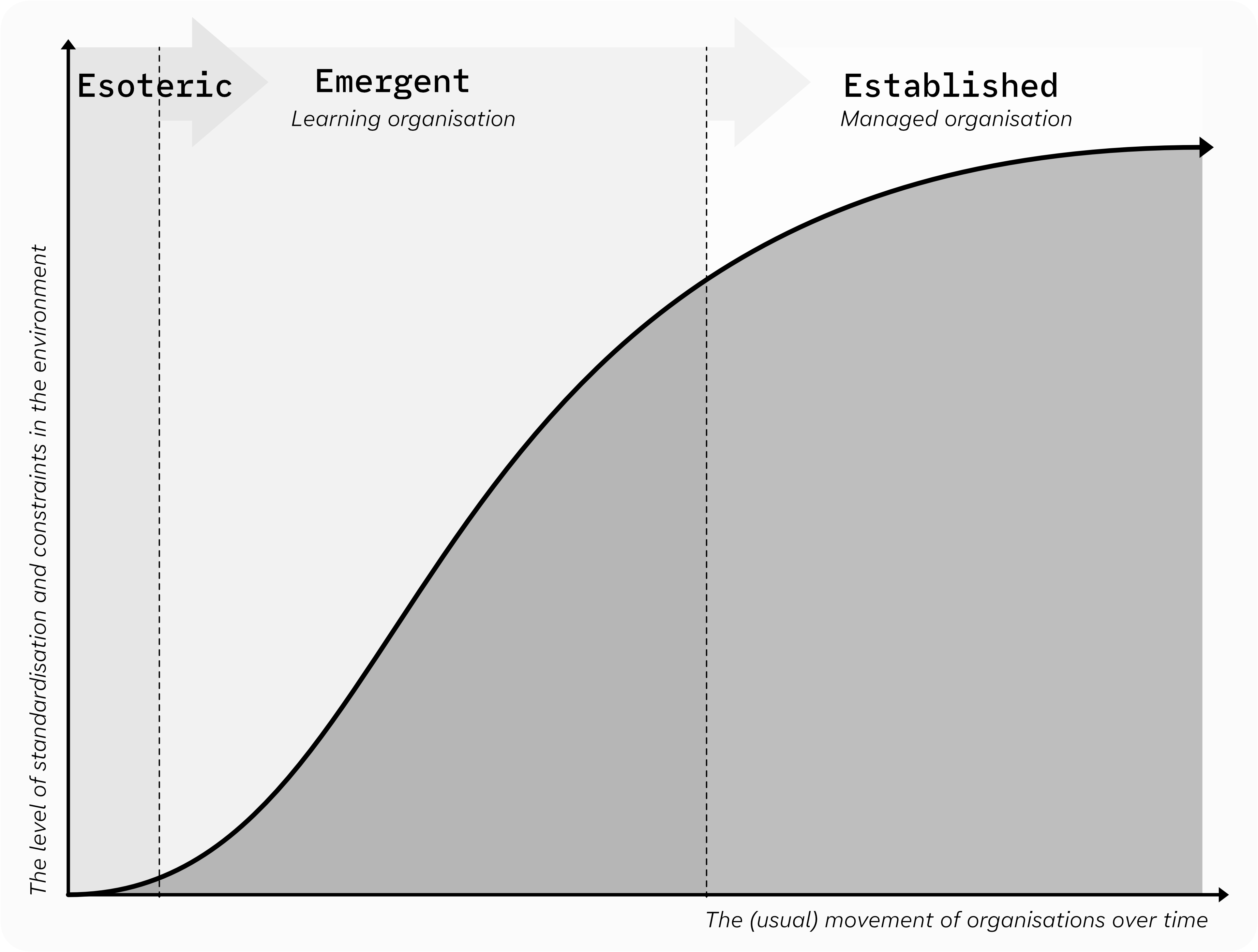

Now in case it wasn’t already obvious, these zones exist on a continuum and the lines I’ve drawn are arbitrary.

The established environment is highly constrained and controlled. There are standard approaches to problems and existing systems with which any changes must work. At the extreme end, the systems are heritage, and no changes are allowed. At the other end of the scale, the esoteric territory (here be dragons) has very few constraints. Opportunities are practically endless, but you must be self-sufficient as there’s no existing system to lean on.

And in the emergent middle zone, you have a mix: some constraints, some opportunity, some infrastructure, some room to move.

Let’s throw that into a model … diagrams are fun, no?

There is not really much to it when you strip away the walking metaphor. But it isn’t always as simple as it seems on the surface, and it might not be as easy as you think to work out where you are!

Let me draw your attention to two things that can trip you up: performative process and the Gotham conundrum. Interestingly, they’re actually the same phenomenon — where much of the endorsed rules

are simply theatre — but from different directions.

Let me explain …

Performative process

There’s a trend for organisations to move from esoteric to established over time. Start-ups might start on the esoteric end of the scale. But if they don’t fail, they’ll take on more staff, add processes and procedures, and all this additional bureaucracy will inherently move them towards becoming established.

And during the process, there will be points where the company will have added processes and practices — all of which give the illusion of establishment — but those practices won’t yet have much clout.

Some examples:

- There’s a community of practice and

endorsed

templates for you to use, but, in reality, the business sponsor doesn’t care what is mandated so you’re not actually going to use them. - There are numerous governance forums to get a release out the door, but people in the know understand that actually just getting Dave to sign off is how you get your release green-lit.

- The CEO could change everything next week!

- There are code coverage rules, but they’re not actually enforced.

- Approval processes are convoluted, and approvals usually happen on paper after the fact.

All of these are signs of performative process. It is theatre. It looks, acts, and feels like an established environment, but it is actually an emergent environment playing dress-up!

The upshot? Just because you can see the process and rigmarole, doesn’t mean that it’s real.

The Gotham conundrum

There’s another interesting phenomenon that occurs when an established environment degrades to the point where the processes, infrastructure, and rules aren’t working. Instead of order, you have anarchy. This can happen because of many factors — change in management, failure to maintain systems, deliberate de-prioritisation of focus — but the effect is the same.

You have Gotham City.

In Gotham City, the processes and rules aren’t actually relevant because law and order has broken down. It’s all just remnants of what worked previously. While big organisations might not wholly degrade to Gotham level, there are often pockets of dysfunction.

The upshot? Just because the whole org is clearly Established, don’t assume that the area that you are working in is.

Knowing what environment you’re in is critical

We are agents of change. We work to identify, understand, and execute change to an environment.

To be effective, we need to be able to assess and discuss the environment: How does it work?

What are the rules?

How can I optimise the path of change?

Knowing what environment you’re in also helps to keep your hubris in check. We all know people who join a company, and the first thing that they do is to try to apply all the things that worked at their last company expecting the same result. Usually without success.

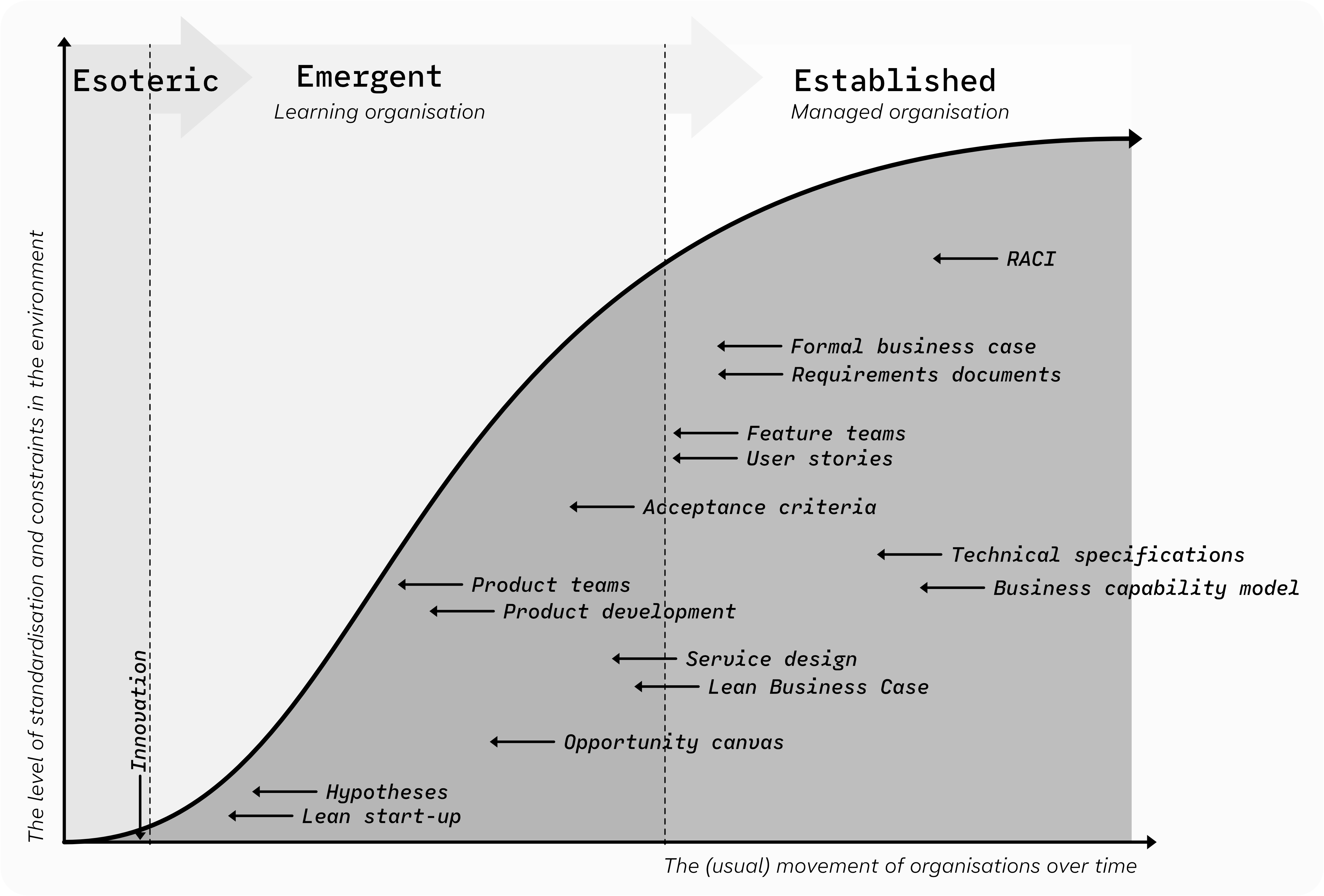

You can see quickly how thinking about our environment highlights themes of practice applicability. Here’s a version of the same model with some practices and their optimal place of applicability overlaid:

Now this model is not intended to be prescriptive — I’m sure the boundaries of applicability could be stretched depending on the situation (plus, I’m sure that we could endlessly debate about where an artefact is placed). I simply wanted to highlight the underlying point: not all tools and approaches apply everywhere.

And the same is true for advice.

Every piece of business analysis content should come with the caveat: YMMV.

Last thoughts!

I’m going to be frank with you, this article was an entirely selfish endeavour.

For years, I’ve fumbled over how to describe a work situation, and similarly struggled to explain the kind of environments in which I thrive. And trying to resolve my own pain point was the motivation to sit down and really think this all through. Once I got going, I was surprised that more hasn’t been written on this topic — if I’ve missed something that you found helpful, then please send me links!

For the most part, I try to keep everything I write about relevant to all types of business analysis in all types of environments. And I suspect that’s true for others, too.

But maybe that’s a problem? Keeping things generic skews towards advice that is only applicable to the established

context — the very thing that I found frustrating as I was starting my career and building my toolkit! And because of the it is applicable in other environments

defence, we don’t criticise some of the unrealistic, heavy-handed, clunky, over-baked, and documentation-heavy practices our industry promotes.

Because there are environments where those practices are helpful.

Just not all.

And that’s the problem.

References

Key references and inspiration for this article include: The Cynefin Sense-making Framework, Situational Leadership, and Wardley Maps. I highly recommend reading about all three - they’re my go-tos when thinking about complexity.

But I also want to take the time to acknowledge a potential criticism of this article, namely, haven’t I just repackaged Wardley Maps’s Pioneer, Settler, and Town planner concepts?

I actually love how Wardley Maps frames situations based on where they are on the path to commodification. He highlights three types of teams:

- Pioneers, who create new and custom products

- Settlers, who use existing products, and

- Town planners, who work on commodified products

Here’s the thing, I despise how that framing inherently idolises colonisation. As a human with eyes from Aotearoa New Zealand, I have seen firsthand the intergenerational negative consequences of colonisation on everyone, and in a world that celebrates innovation, equating innovation and invention with the act of settling it

, is frankly gross.

And even more so with the current world events.

So I refuse to use it.

But since the underlying concepts from Wardley Maps were such a massive influence on this thinking I feel I have to acknowledge the reference (yes I did reference Wardley Maps a ton here!), and address the concern (see above).

Hopefully that makes sense! Words matter, y’all!

Last updated .