When Things Are on Fire: Practical Advice for Challenging Projects

An illustration of a snakes and ladders board, some dice, and some instructions titled Help! My project is on fire!

Three out of every four projects fail. Some limp over the finish line and people only really notice that the project failed to deliver the expected benefits after the launch party is a fond and distant memory.

Others are absolute first rate dumpster fires.

If you work anywhere near change, in and around projects, or are the manager in a large enough organisation, then these statistics matter because statistically speaking, you will find yourself on a dumpster fire of a project at some point, if not more than once.

So knowing what to do is helpful.

This article is the written version of a talk — What to do when things are on fire! — that I gave at a recent conference.

What we’ll cover …

The talk (and this article) has 4 main parts, bookended with an intro and a postgame commentary.

- Part one: Should you even play the game? examines the painful reality of working on a project that’s on fire, and considers whether it simply isn’t worth the effort.

- Part two: Rolling the dice is all about the most important element of the game: you! We look at how to stay sane under pressure, and how to vent without getting caught in a death spiral.

- Part three: Game play broadens the view to consider about your team. How can you help them cope? And how can you get them all on the same page?

- Part four: Winning the game is all about the project itself. How do you resolve the big issues? What do you need to ensure a win?

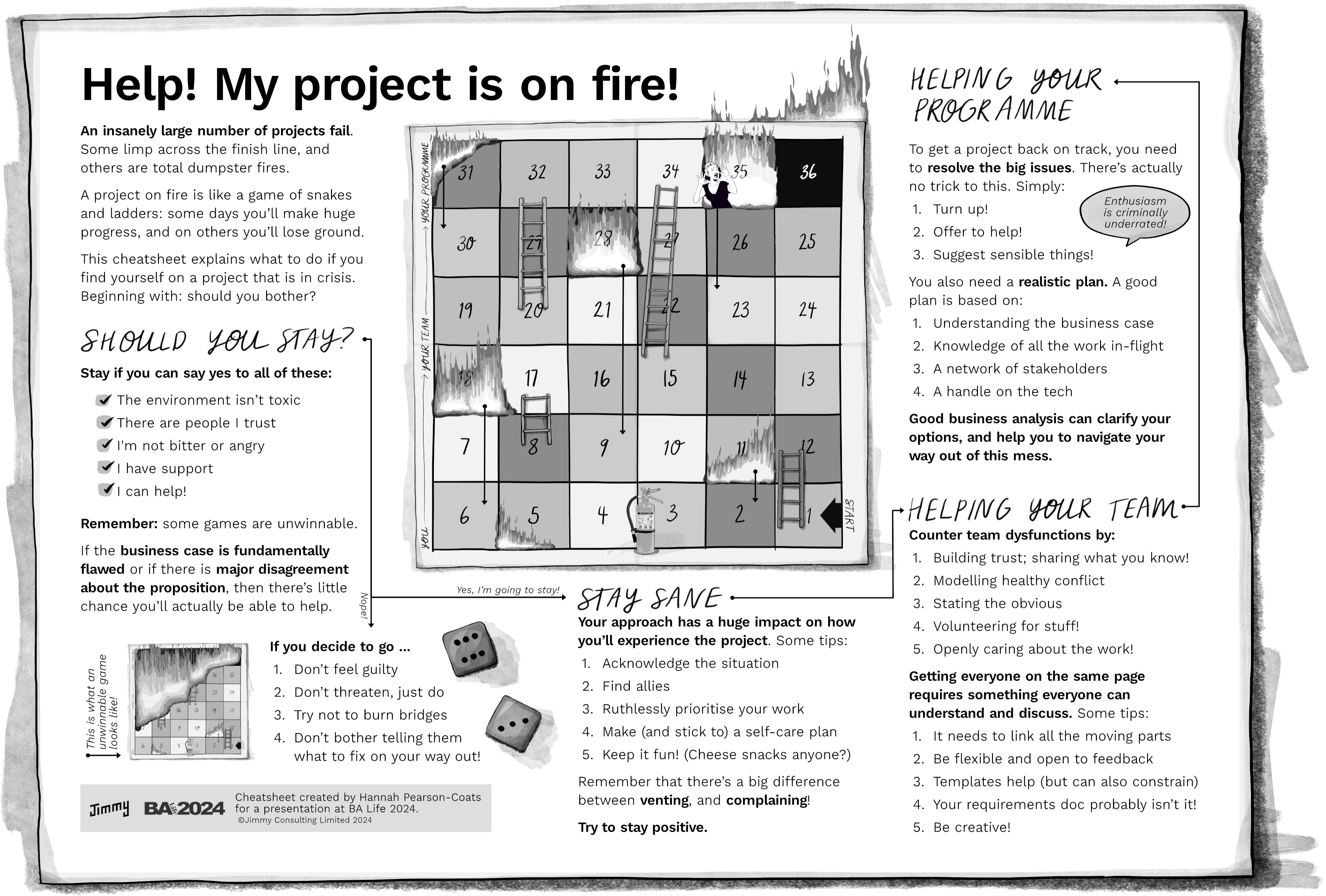

Or, if the 4000+ word length of the text below is too daunting, then I’ve summarised the key points (minus any narrative or context) in a downloadable cheatsheet! 👇 Worth keeping handy for easy reference.

Every project is unique!

No two projects are the same. Context, politics, personalities, deliverables, and all manner of nonsense make giving practical advice challenging. But we can solve that problem by talking about projects using a suitable (but also cute) metaphor: a game of snakes and ladders.

Which works … no?

Working in a project that’s on fire has a huge element of chance, and along the way you’ll find things that move you forward (ladders 🪜) and others that will cause you to lose ground. Except in our game, instead of snakes, it’s the squares on fire you need to keep an eye out for. 🔥

And we can use the metaphor of the game to talk about different elements that matter:

- The environment (the board)

- You (how you choose to play)

- Your team (making progress on the board)

- The project / programme (actually winning the game!)

I know it’s a lot to cram into an article, but I’m committing! And the only way to start is at the beginning. Which is precisely when you should ask yourself: Do I even want to play the game?

Part one: should you play?

Challenging projects are not fun. Here’s some quotes from people I talked to who have real world experience working on a project that was on fire:

It was crushing, I wanted to leave …

I was continually expecting something to go wrong, or to find that I’d missed or forgotten something, so super stressful on the inside.

Who’s going to be the next to burnout?

Man this is deflating

How did we get this so wrong??

I felt like a total failure.

Oof. That last one is a real gut punch isn’t it?

Like I said, challenging projects can be deeply unfun. And while the ability to leave a challenging project is itself an act of privilege: I’ve seen a lot of people fail to realise that it is an option.

And to be clear, throwing your hands in the air in disgust is always an option. It might not be a particularly attractive option, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t a real option. Even if you aren’t in the position to get out immediately, you can start laying the groundwork for an exit.

That said, making the decision about staying or going can be tough. So I made a checklist of the key things you need to consider:

The should I stay

checklist

If you can’t say a confident yes to the following statements, then you should consider how to get out.

- It’s not a toxic environment

- There are people I trust

- I’m not bitter & angry

- I have support

- I can help!

And before you confidently declare that you have passed my test with flying colours, I want to spend a little bit of time on #5 above. Because sometimes thinking you can help is very different from actually being able to help.

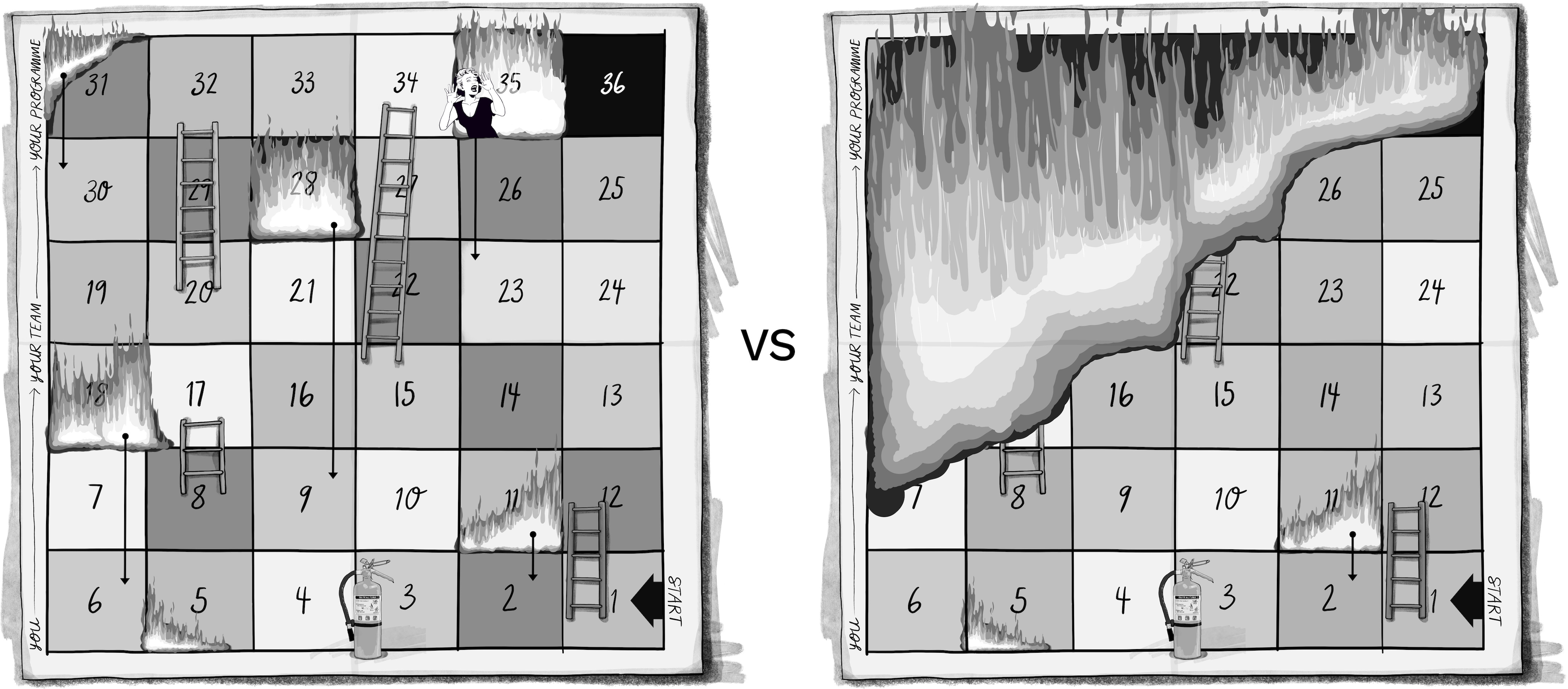

Some games are unwinnable!

There’s a huge difference in your chances of success between the following two game boards. One is winnable (but you’ll have some challenges along the way). The other is borked. No matter what you do and how well you play, you will not win.

The question you need to ask yourself is this: is the project simply off track but winnable? Or is it fundamentally flawed and unwinnable?

And there are two types of fundamental flaws that you need to look out for:

- The business case is flawed. The proposition isn’t clear or doesn’t make objective sense.

- There isn’t foundational alignment around the proposition. There isn’t consensus about the core approach to delivering the solution (such as platform choices). The business is not all on the same page.

If your project suffers from one of these, then it is incredibly unlikely that you’ll be able to help the project get on track unless you have incredible influence over the project. I’m talking business-sponsor-level influence here. Real talk: if you think the project is in one of these situations, take a hard look at what is possible and ask yourself honestly if it is worth sticking around.

And if you do decide to leave, some suggestions:

- Don’t feel guilty, it’s just a job!

- Don’t threaten, just do it.

- Try not to burn bridges.

- And don’t bother trying to tell the team how to fix things on your way out the door. That’s pointless. Either stay and help fix, or let it go.

But let’s assume that you are saying a confident YES to all five items on the checklist and you’ve decided to stay! That’s exciting!

Time to roll ’em dice!

Part two: rolling the dice!

Now that you’ve chosen to play, we need to talk about the most important element in the game: you!

It’s far too easy to forget that you’re a player in the project on fire game. And it is way too easy to slip into the mode of it is happening to me rather than the mode of I’m freaking happening to it!.

But the truth is that — bar none — you have the biggest influence over how you experience your time on the crisis-project. You are the person rolling the dice. So we need to make sure that you’re in a good place before we tackle the team or the project.

The old adage of put on your own oxygen mask first

is totally relevant here, so here are some tips for staying sane when things around you are on fire:

First, acknowledge the situation! There’s a really good reason why all the AA programmes and the like start with admitting the facts … it actually works! If you can’t genuinely acknowledge that you’re on a project that’s on fire, then there’s no way that you can meaningfully get it on track.

Second, find allies — people you trust and to whom you can vent! Now, for some personality types this is less necessary than others, but it is (in my experience) always valuable!

Third, ruthlessly prioritise what you put effort into! It is far too easy to slip into an overtime mode to cope with your usual work plus all the extra fire-fighting on top to feel like you’re in control of things. That’s a bad plan and is unsustainable. Failure to prioritise and just working longer hours is actually prioritising short term benefit, over longer term gain. You need to let go of some things.

My most successful application of this was on a project where I would turn up to my morning meeting with the Programme Manager (and my boss). I would of course, always bring my laptop. On the top of the laptop would be post-it notes with all the activities I could do that day and I would declare that at most I can do two of these

.

My boss somehow always managed to convince me to take on three post-it notes, but that is beside the point. The point is that there were at least four other post-it notes that my boss was acknowledging weren’t going to be progressed today. Together we agreed on what was important, and what wasn’t. As a result, I could go home for dinner rather than be a slave to my desk!

Fourth, create (and stick to) your self-care plan. I don’t know what your self-care looks like … it might be the gym, it might be time with your kids, it might be interpretative dance to spoken word poetry while wearing a bird suit. No judgement here. The point is that you know what keeps you sane and what doesn’t and you do you!

Lastly, regular cheese snacks can help! And by that I mean, you need to find enjoyment. For me enjoyment is cheese snacks (and if you know me also dumplings - which is clearly the food of the gods!). For you, it might be yoga on the beach, or sky-diving, or dad jokes in the team slack channel. It doesn’t matter what it is, Success doesn’t mean merely that you stay sane, but that you aren’t hating every minute of it.

And let’s be honest, if you have lost all the enjoyment, then you have lost the game no matter what the outcome of the project is!

If you manage to apply these tips, you’ll be more resilient, more stable, and better able to bring your best self to the firefight. But there’s one other thing that will help you to stay sane: understanding the difference between venting and complaining.

Venting vs. complaining

Venting and complaining seem like synonyms, but they really aren’t. Complaining ends with oh man they’re just the worst

, whereas venting ends with You got this, go get ’em, give ’em hell!

See the difference? Both get stuff off your chest, but only the latter leaves you empowered.

When you’re complaining you’ve a victim. Things are happening to you. Agency exists elsewhere. You’re not in control. Complaining might feel good for a short bit, but leaves you feeling resentful and frustrated. Venting is far less problematic. Venting achieves the goal — you get stuff off your chest — but maintains your agency. You’re left feeling lighter and ready to jump back into the fray.

Or to put it in the words of a colleague: Venting is a pit-stop. Complaining takes you off the track.

Getting these two confused can have some interesting and unhelpful consequences. You can sink into a death spiral of negativity and end up missing the positive changes happening in the project. And the risk is that you’ll self select out of the team that is actually solving problems. Where you want to be is absolutely on the team that is getting the project back on track!

It’s worth remembering that how you respond and behave drives how people experience you. Or to use the words of someone much more excellent than I:

They may forget what you said — but they will never forget how you made them feel.

This is as true when you’re playing a game of snakes and ladders, as it is on a project that’s on fire! A year down the track people won’t remember whether you won the game, or if your artefact was the key to solving the big issues on that project, but they sure as chips will remember what working with you was like.

And you are a wonderful human with skills who can help. And you will help! So stay positive!

Now, if you’ve got yourself sorted, it sounds like you’re really play the game. Let the fun begin!

Part three: game play

Getting yourself sorted is all preparatory to making actual progress on the board. You might be able to survive several rounds of the game solo, but that won’t get you far. You need a team to make real progress.

But if your project is on fire, then your team might be in trouble.

’s The Five Dysfunctions of a Team is a useful reference to understand and diagnose what might be going on with your team. The five dysfunctions are:

- Absence of trust

- Fear of conflict

- Lack of commitment

- Avoidance of accountability

- Inattention to details

In the model, they compound. So if you have absence of trust, then you’ll likely to have fear of conflict, and if you have those two, then you’ll probably have lack of commitment … and so on. Here’s the thing: aren’t these all pretty reasonable responses to stress and pressure?

And what can you do about it?

When things are going sideways, there is huge opportunity to lead by example. Because the truth is this: the vast majority of people want to be on the right side of history. They want to be on the team that fixes things. They don’t want to continue working in a dysfunctional environment.

They just need the opportunity to be excellent!

And that’s where you can help.

Lead by example!

The five dysfunctions can help you to frame how to lead by example.

To counter the absence of trust, actively build trust through transparency and openly sharing information to which you have access. Work in the open, and trust your team with your work in progress.

To tackle fear of conflict, model healthy conflict. I don’t mean that you should be disagreeable to show how to disagree, but you’ll need to be able to share and discuss challenges to navigate your way out of this mess, so do that. Welcome feedback (even if it makes your heart sink). Encourage voices to share. Celebrate when you discover more problems — it’s actually a good thing because now that you know what’s wrong, you can plan how to minimise the carnage!

This takes practice. It is difficult to stand still and listen to someone tell you that your idea will fail while calmly responding with Oh! Interesting. That’s not how I was seeing it because of X, Y, and Z, so let’s unpack that to make sure we aren’t missing something …

To address lack of commitment by the team isn’t easy. One lone person can’t model their way out of this. You cannot make the team commit. There’s a ton going on here, but the easiest thing you can do to help the team to get back on track is to state the obvious. In a healthy environment, much can be left unsaid. This is not true when you are in a crisis. And that is especially true when it comes to how someone’s work is contributing to moving the team forward — or not.

So, don’t hedge or hide. Say the obvious, say what you’re seeing, what you think is happening, and how you see your work helping. Saying isn’t committing per se, but it’s a step closer. And every step counts.

Countering avoidance of accountability is easy. Volunteer for stuff! And then do it! Own it! Job done!

And lastly, to address inattention to details, simply care openly about the work. Caring about the spelling mistake in the report and keeping your tickets up to date are little things, yet they speak volumes. Make your work shine. Help your team see that the work still matters. But be careful to not police other’s work, just your own.

Getting everyone on the same page

But even as you tackle your team’s dysfunction, there’s the actual project work to do, no?

On projects, especially ones that are under pressure, people tend to be spread thinly. And in the areas where people aren’t paying attention (the gaps), issues tend to fester. It usually isn’t that the design is bad; it’s that the design is incompatible with the architecture. Or it isn’t that the research isn’t finding out really helpful things; it’s that the research isn’t be utilised by the other team.

It is in the gaps that things smoulder. Any one of those smouldering fires could flare up and become the next big project issue.

You want to find out what is smouldering at the earliest possible opportunity. The sooner you find out, the better your chance of tackling it before it does actual damage. To get on track, you need to be able find and surface the big issues.

And to do that you need everyone on the same page.

It is only when everyone is talking about the same thing that you’ll uncover those big smouldering issues that can hurt you. You need to know which squares are on fire in your game of snakes and ladders to avoid landing on one.

Getting everyone on the same page is the real trick!

To do this you need something that everyone can talk to.

It doesn’t matter what it is, it could be a scribble on a whiteboard, a paragraph in a Google doc — I’ve even seen a metaphor work (yes really!) — as long as you are all able to stand (virtually or otherwise) around a thing and discuss it, you’re on the right track!

This sounds much easier to do than it is in practice, and it gets progressively harder as the project gets bigger. It is much easier to get a small team of five on the same page than it is to find something that designers, architects, programme managers, developers, testers, business reps, and all the other flavours of project peeps can engage with! That’s a big trick!

Some tips for getting everyone on the same page:

- First up, it is super unlikely that your existing artefacts are going to be the magic thing to bring people together! The business case or your requirements document just isn’t going to be it! The act of creating it together is key.

- Make sure that whatever you use links to all the moving parts on your project. It has to work across multiple domains, not just one. Cross functionality is critical.

- Be flexible and open to feedback. Fold in perspectives as you collect them.

- Remember: templates can help, but can also constrain. It is more important that it works, then it looks good on your portfolio.

- Be creative! I once ended up with a diagram that was nicknamed the rainbow sausage because of the colour scheme and general shape. It wasn’t a diagram based on any standard modelling approach. It was simply a summary of alllllll the key information about the systems and teams. I hated the nickname, but if the CTO finds a thing useful enough to give it an amusing name … well then that’s what it is going to be called, I guess.

And while every project is different and I don’t want to advocate for a specific approach (see #5 above), I’ve had the most success with approaches such as service blueprints, customer journeys, concept models, and story maps. These types of artefacts seem to work for many different people across the team.

Get everyone on the same page and you will have made major progress toward winning the game.

Part four: winning the game!

The objective of any project is actually to deliver benefits.

The good news is that everything we’ve discussed up until now — the tips for staying sane, how to counter team dysfunctions, how to get everyone on the same page — is as true at the project or programme level as it is for you and your team.

Keeping sane, modelling healthy team interactions and behaviour, and getting everyone on the same page are all key to helping put the project fire out.

But with an important caveat … The greater the height, the bigger the fall!

Unless you know exactly what you’re getting into, getting involved in the project-level shenanigans carries risk, especially if everyone is in a panic. Generally, you’ll find more politics and ego the higher you go in any game. You’re as likely to be knocked off your ladder by accident as you are to wander into a fire that you can’t escape. All I’m saying is proceed with caution.

But let’s assume that you’ve managed to navigate that complexity …

How do you actually get a project back on track? Great question! The answer is simpler than you’d expect. You only need two things:

- The big issues resolved, and

- A realistic plan!

The big issues

The big issues are usually boring and generic. They’re things like:

- Scope is not well understood

- Timeframes and budgets are too tight

- Technical complexity was underestimated

- Core assumptions are wrong

- You can’t get the right people and skills to do the work

But let me tell you, not only do these issues feel extremely unboring when experienced on the ground, but they also cause all manner of consequences throughout the project. In fact, you can easily get distracted from these core underlying issues by fire-fighting the symptoms these issues create. Don't get distracted by a burning lawn chair if the house is in flames!

But how do you actually tackle the big issues?

There’s actually no trick here. It doesn’t matter what your role on the project is. Simply continue to turn up. Offer to help. Suggest sensible things. And respect that you can’t be involved in everything.

And if you have have a role that can steer and/or direct attention, then there’s added advice for you:

- Make sure the issues are visible

- Help your team to focus on the biggest issue

- Ask what they need to solve it

- Run interference with outside players

- Get stuck in (see advice above)

This advice sounds boring and simple, but it works! We like to overcomplicate things when we shouldn’t. Basics get the job done.

Dealing with the big issues is key because only when you’ve resolved them can you build a plan that will work.

Build a realistic plan!

The second ingredient that you need is a realistic plan to get yourself out of this mess and to the finish line. And to build a good (and realistic) plan you need:

- Deep understand of the business case

- Knowledge of the in-flight work

- A network of stakeholders

- A handle on the tech

You — or whoever is in charge — need to pull the necessary people together with the understanding of all to pool information into a realistic plan. So, if you’re in charge, then get the necessary people together, and if you’re not, then advocate for it to happen.

Or just do it anyway!

I’m obviously skipping over the huge chunk of work where the realistic plan is socialised and the key stakeholders actually buy into it (which can be super challenging, especially if you’re having to explain how you won’t be able to achieve the outcomes they thought they’d be getting). But if the plan is realistic, based on facts, and provides a clear path to winning the game (and assuming that the previous plan would not) then really, apart from pulling the plug on the project, the truth is that the stakeholders don’t really have a choice.

And if you’ve got a plan, and you’ve dealt with the big issues, then the rest is just regular project management to the finish line!

You’re back on track to win the game!

Postgame thoughts!

You’ll notice that I haven’t included any advice on downing tools, or doing a project reset, or how to rebuild trust with client/business reps. The reason is that all advice about that is situational.

But there are two pieces of advice that are universal.

1. Good business analysis can help

Sorting out the issues and building a plan requires you to make a bunch of really good decisions quickly. Good business analysis will help you clarify your options, and will help you to navigate your way out of this mess.

I know, I know, my background is in business analysis, so of course I’m going to say that. But the second piece of advice isn’t related to business analysis and is perhaps even more important …

2. Enthusiasm is criminally underrated

To stand in the face of uncertainty, roll the dice anyway, and deal with the consequences requires resilience. But it isn’t resilience that gets people going in the morning. It’s enthusiasm.

People respond to enthusiasm. They’re inspired by it. They want to get on board. They want to help. Enthusiasm can help people to navigate through all the uncertainty. And I don’t mean a toxic-positivity kind of cheer-leading false enthusiasm. Genuine, frank, honest enthusiasm is what gets the job done.

There’s incredible power and leadership in being the person who says: This is borked … let’s fix it!

Lots of people say the first part. Be the person who says the second.

Last updated .